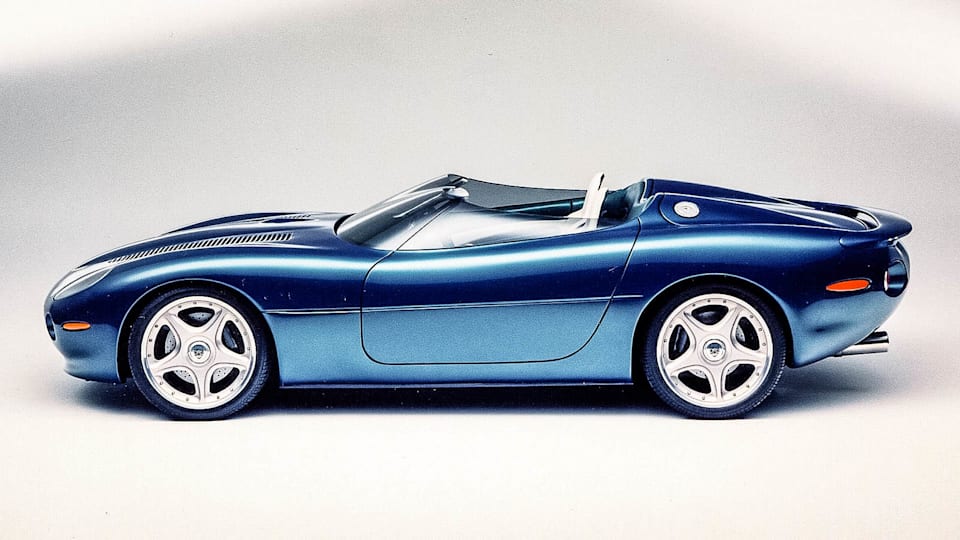

The body began to take shape in early May, and by mid-June it was ready for painting. As in any concept car, colour plays an important part in the overall design, and Keith Helfet’s choice looked back to one of his favourite Jaguars. the D-Type. Helfet selected a paint that combines echoes of the metallic blue of the Ecurie Ecosse D-Type which won at Le Mans in 1957 with undertones of green and gold. It is a colour which would have been impossible to achieve in the days of the XK 120, and is one of the most obvious signs of Nineties technology in the new car.

By now the mule was racking up the miles necessary to test and fine-tune the engine and chassis modifications. All these modifications had been carried out by engineers at Jaguar’s Technical Centre at Whitley, and they were designed to add power and performance which would match the car’s image and heritage. Engine modifications increased the 370 horsepower available in the production XKR to an even more impressive 450, while racing suspension with adjustable dampers and larger brakes, wheels and tyres ensured the extra power was well controlled. Using the handling circuit and the high-speed track at MIRA, the engineers began to fine-tune the modifications in order to come up with a specification the SVO workshop could follow when the time came to start building the car.

Meanwhile, Helfet and his colleagues began to work on the cockpit design, styled, like the exterior, with a retro-influenced cloak over modern technology. Ergonomics were important, as were looks, but Helfet’s design policy was also heavily influenced by tactile sensations. “I wanted everything you touch in the cockpit to be metal or leather,” he explains. “It formed all my ideas about the instrument-panel, where I wanted the switchgear to have a look and – just as important – a feel of past Jaguar sports and racing cars.”It took four weeks to design the interior and another two weeks to create the moulds that would be used to form the necessary panels. It was now July, and the Paris launch date was less than three months away. But everything was coming together according to schedule, and final assembly of the car was under way under a cloak of secrecy in the SVO workshop. While the body-men assembled the aluminium panels, the chassis specialists were building up the special components Whitley had specified to achieve the required handling. The specially-prepared AJ-V8 engine was installed by workers who had started at Jaguar when the six-cylinder XK power unit was Jaguar’s mainstream engine, while trimmers who had shaped the leather to cushion royalty and statesmen set to work on the racing seats and harnesses made necessary by the new car’s performance. In the electrical department, work began on adapting switches with the style of the Fifties and Sixties to operate with Nineties technology. It was not an easy task, for even such an action as turning on the headlamps of one of today’s Jaguars involves more electronics than were to be found in a complete XK 120.

Working with outside specialists who supplied such components as the wheels and the uniquely-shaped windscreen. SVO worked throughout July, August and the early part of September. By the middle of the month the car was ready to be photographed, and in the following week all the tiny detail jobs were completed before it was carefully loaded for transport to the Motor Shows.